Preface:

Tending livestock on an Iowa farm during the winters of the 1950s was an arduous and monotonous task. These are my memories of tending to water tank heaters for the hogs and cattle.

Light, Dammit, Light

I was a farm kid in central Iowa during the 1950s; the ‘50s when we had real winter. Snow so deep it was up to the barn roof. The cold north wind packed snow drifts so hard the livestock walked up and over the fences. It didn’t just snow. We had blizzards and lots of them. Cold, it was so cold if you sneezed the spray turned to ice pellets. When I complained, dad would say “Well there’s nothing between us and the North Pole except for a woven wire fence.” As I looked out over the snowy and flat farm fields, I knew he was right.

We raised hogs, a few cattle, and a dozen milk cows. Our livestock shed provided shelter from the wind and snow. Half the shed was for cattle and the other half for the hogs. In the really cold weather the cows, that were milked by hand, were kept in the milking parlor of the barn. Cattle and hog feeders were outdoors. In the ‘50s, confinement buildings were somewhere in the future. Hogs required water and feed on a daily basis. The feed wasn’t much of a problem. Ground corn, oats, and protein came out of the feeder regardless of temperature. Water however, was fickle. Below 32 degrees it became hard water, as we called it. The hogs and cattle couldn’t drink hard water. The winters presented real challenges with water.

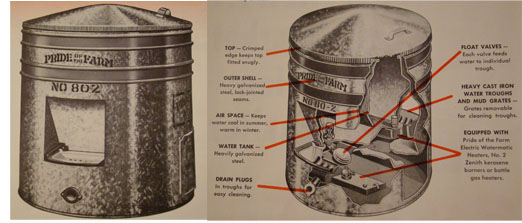

One of my jobs was to make sure the water didn’t get hard in the hog waterer. Our hog waterer held 100 gallons. When the temperature

I filled the hog waterer out of the stock tank the cattle used. I dipped a five gallon bucket in the stock tank. I lifted it out, pivoted on my left foot, and dumped it into the hog waterer. I wore yellow cotton gloves like most farm workers. I carried several pair with me. You can still buy those gloves today, but now they are

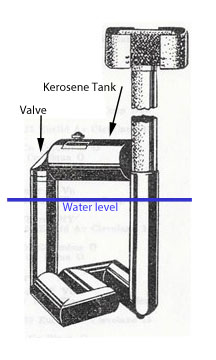

With the waterer filled it was time to fill the heaters with kerosene. The heaters were basic tools. Imagine your great grandmother’s kerosene wick lantern she used in the house for light before electricity. Now remove the glass chimney from the lantern. Now remove the ornate glass container

I begin the job by putting my wet gloves on top of a wooden fence post and putting dry gloves on my hands. Rubbing the dry gloves together relieves the shock of the cold wind blowing on my wet hands. Next I get down on the frozen snowy ground on my hands and knees. Now days I can still do that, but I can’t get up. I remove the access door located at ground level. I look in and see both heaters still burning, a good sign. The water in the trough is not hard. I lay down on my left side and get my body situated between the waterer and the woven wire fence. I reach into the waterer with my right hand and slide one of the heaters toward the opening. I blow out the flame. It’s not safe to have an open flame around fuzzy yellow cotton gloves or spilled kerosene. Most of the time I didn’t have to blow out the flame. The wind did it for me. Your first clue to “not easy.” I repeat the process with the other heater.

The next step was to remove the screw-on cap or the cork. Corks replaced lost caps. The fill opening of the heater was small. I filled a quart oil can with a flex spout from the nearby kerosene barrel. I carefully poured kerosene down the spout into the small opening, and filled the heater. I was careful not to spill kerosene on the heater or on me. It was undesirable to have kerosene puddles or soaked clothes when I got ready to strike a match to light the heaters. Your second clue to “not easy.”

Prior to lighting the heater I pulled the glove off my right hand; hopefully, it was still dry and not soaked with kerosene. I unbutton the side of my coveralls and reach into the right front pocket of my blue jeans. I extract my pocket knife. I still carry a pocket knife in that location every day of my life. In the 1950s no self respecting school boy would admit to not carrying a pocket knife. Father’s enforced the rule to never threaten someone with a knife or to use it for anything mischievous. I never remember a kid who needed a second chance. You just never broke that rule. Those were the days of respect for others and self respect. Idiotic zero tolerance rules were not required back then. I digress.

I opened the long blade of the knife and trimmed the wick. I cut off all the ragged and charred edges. A well trimmed wick was flat and straight. This produced a uniform and long burning flame. A flame that kept the water soft all night and all day. A successful trim job included no cut gloves, no cut fingers, and definitely no blood. Although at twenty below zero cold, blood vessels were so constricted there was little blood loss. Another clue. Are you getting the idea of not easy? The worst is yet to come.

With the wick trimmed, the heater is ready to go back inside the hog waterer. I check the wind direction to determine how I need to place my body. Trees and shrubs are not the only wind break. I lay down on the cold snow covered ground to shield the access opening from the

I lay down on the ground, shielding the wind, and reach into the waterer. As I reach, the collar on my coat shifts and the wind blows snow down the back of my neck. I shiver and grimace. I’m shivering too hard to swear. I strike the match across the rough cast iron surface of the water trough. The match ignites, and the air fills with the smell of burning sulfur. Yuk. Quickly I move the match to the wick. Just before the match gets to the wick a gust of wind comes over my back, through the access door, and blows out the match. If Dad wasn’t around I would talk to the wind in one syllable words.

Time to roll over on my back, unzip, reach deep into my dry clothing and retrieve another match. Now it was time for reason and logic to overcome mother nature. Accurate timing was the essence of success. I check the wind direction again, and I positioned my ample chest and belly to block the wind. I waited for a gust of wind and checked my body position. I was in the right place. I waited for the second gust of wind. Aha, now I had the time interval between gusts of wind.

In that interval I could strike the match and light the wick. The plan was ready so I waited for the next gust. It came just as I expected. I struck the match, and more sulfur smell filled the air. I move it quickly to the wick. But damn, an unscheduled gust of wind blew it out an inch short of the wick. Failed again. A flurry of one syllable words escaped my mouth. (The line “You’d be better off to try to rope the wind” from the song “Whatca Goona Do With A Cowboy” by Chris Ledoux always makes me think of lighting hog water heaters)

Once again, roll over, unzip, reach deep, retrieve a match. Rezip, wiggle around on the cold snow, but heck, I’m numb by now, and position my body. Good thing we didn’t know about wind chill back then. It was either cold or damn cold. Today it was damn cold. I time the gusts, I strike the match, move it quickly, and the wick ignites into a beautiful flame. I turn the knob to adjust the flame. Too low is not enough heat. Too high is a smoky flame that will char the wick and eventually go out. I get it just right. Success. The water in that trough will stay soft. Now, it was time to attack the second heater.

The second heater was on the opposite side of the water tank. I fill it. I dig down for a dry match. I position my body and strike the match. I move it quickly to the wick. The wick doesn’t light. I slide the match back and forth across the wick. The match stick flame is getting closer and closer to my cold numb fingers. I holler “light, dammit, light.” The wick erupts into a flame. Success followed by a grumble of “it’s about time.” It isn’t easy, but it’s done. Tomorrow will be the sequel. The movie “Ground Hog Day” ain’t got nothen on kids that had to light hog water heaters.

I crawl up off the snow covered ground and brush the snow off my coveralls. I pick up my wet, now frozen, gloves from the wooden fence post and climb over the fence. The cattle tank heater is next.

I open a door on the cover over the cattle tank and reach for the heater. It is stone cold. The fire has gone out, but luckily the water is still

I take the fuzzy yellow cotton glove off my right hand that is almost warmed up after doing the hog waterer. I strike the match on the side of the fuel tank. The flame and sulfur smell jump out. I hold the match until the match stick ignites. Being quick and careful, I hate burnt fingers, I turn the match on end with lit end down. I drop it down the middle of the pipe hoping for a direct hit in the fuel pool.

The burning match lasts long enough for me to see the pool of fuel. Out of nowhere a gust of wind sweeps over my back and down the pipe. The match goes out just before it hits bottom. I turn the kerosene valve to off. Too big a fuel pool will harm the heater when it ignites. I close the doors on the cattle tank and trudge through the cold blowing snow to the barn.

I unzip, unbutton, and refill my shirt pocket with dry matches. The cows in the barn keep it warm. I pause to warm my hands and chilled body before wading through the snow to the cattle tank. As I open the barn door, I am greeted with falling snow. Whoopee.

Back at the cattle tank I check the wind and I time the wind gusts. I figure with my luck a big snow flake will land on the match just as I strike it. I strike it, the snow flake misses, I get the stick ignited, turn it, aim it, and drop it down the pipe. The match hits bottom but off to the side of the fuel pool. Bad aim and I search for new one syllable words.

Again unzip, reach deep, find a match. I strike it, turn it, take aim, and drop it. But this time I apply body english. The match hits the middle of the fuel pool and falls on its side with the flame still burning. I holler “light, dammit, light.” The fuel pool ignites and the burn pot glows. Success has almost arrived. I reopen the valve to achieve a slow steady drip. The frigid air drafts down the fuel pipe, across the burn pot, and up the chimney. The fire in the burn pot is steady and not too much smoke out the chimney. Success.

I trudge off to the house and go down the basement stairs. I lay all my gloves, wet, frozen, or otherwise, on the exhaust pipe of the furnace. They will be dry and warm when I start this all over again tomorrow after school. Filling and lighting water heaters was a miserable job. However, it was preferable to the summer job of walking beans.