Preface:

The aromas and sounds experienced by farm kids in our youth of the 1950s and 1960s will live in our memories forever. With work, a few can still be found but many have faded into history. This story will energize your memories of the greatest time in our lives.

Farm Aromas and Sounds

During my youth, the aromas and sounds of the farm gave me productive skills. Many of those skills have been almost lost to today’s youth isolated in tractor cabs and dependent upon technology to manage farm machinery. The skills acquired on the open seat of a tractor via sight, hearing, taste, touch, and smell, help us “old” guys and gals keep up with the “techies” of the 21st century. We learned skills of safety, enjoyment, contentment, contemplation, observation, common sense, and how to solve our own problems.

I grew up on an Iowa farm during the 1950s and 1960s. After World War II, farm power was in rapid change from horses to tractors. I remember when my dad used horses to plant and cultivate corn. He said it was easier to get the horses to go in a straight line than to steer the tractor in a straight line. My dad was not a believer in the philosophy that there was more corn in a crooked row. A straight row was a sign of a good farmer. Driving in a straight line was almost a religion for my dad. In those days, there were lots of aromas and sounds that have been displaced by “modern technology.” Those aromas and sounds gave my generation coping skills that did not require batteries, computer analysis, or a wireless connection. Many of today’s generation become helpless with the loss of electricity or a wireless connection.

My favorite job on the farm was plowing, especially fall plowing. The weather was cool, the smell of fall was in the air, the leaves were turning, and the harvest was done. Some mornings the ground was covered with a sparkling white carpet of frost. We had three tractors each capable of pulling a three bottom plow. That was a big deal in the early ‘60s as my dad, my brother, and I plowed down the corn and bean ground after harvest.

444 Massy, 300 IH, 350IH Utility

These were the days before tractor cabs. We sat out in the open on the tractor seat. The sun, wind, sounds, and aromas surrounded us. Our five senses delighted us as they gathered data that required only the computing power of our brains. Cold and windy days were sometimes hard days. The cold wind would cut through all four or five layers of clothing. When the weather turned really cold, we put heat housers on the tractors. They were constructed of canvas and a simple wire rod frame. They covered the engine and funneled the warm fan blast of the engine toward you.

When driving into the wind, you could get warm. The cold wind blew up the open back of the tractor driving with the wind. You got cold but just counted the minutes until you could turn around and go the other way to get warm again. Heat housers were such a great comfort I wondered what else anyone could want on a

Photo credit: yesterdaystractors.com

tractor. Little did I know my future would be part of a team designing tractors with a cab providing a comfort level similar to the family’s living room.

When plowing in the fall, you could hear the sound of the plow’s moldboards breaking the soil. You could hear the sound of the coulters cutting the corn stalks. You could hear the sound of the engine lugging down in tuff spots. In those days there were no tachometers on tractors. You depended on hearing the sound of the engine to know when to downshift and upshift. Most tractors had four or five gears, two of which were useful for plowing. Mechanically shifting gears at the right time was an art requiring considerable experience to acquire. Tractors with cabs, 16 speed automatic transmissions, and a gazillion sensors have eliminated all the fun, and the art, of shifting gears. One day I discovered a new sound of plowing.

I had been off the farm for several years. A newspaper article told about the national plowing matches being held on a Saturday about an hour’s drive away. I decided to go. When I arrived, I discovered they were also having a contest with plows drawn by horses. I had heard my dad’s stories about plowing with horses when he was young. Dressed in my John Deere baseball cap, tee shirt, blue jeans, and work boots I meandered across the field to the site of the contest. I watched in awe as the plowmen handled their horses and plow with great skill.

I became aware of sounds that I hadn’t heard when plowing with a tractor. The first was easy; it was the jingle of the harness on the

Many years have past since that day. My hearing is not what it used to be. But, I still recall the sweet sounds and melodies of that day. A group of spectators, both younger and older than I, stood quietly while we soaked in the sweet sounds of days gone by. Sound was only part of the joy. The aromas were also a big part plowing. The aroma of freshly turn soil was pleasant upon my nostrils. Farm kids know this aroma. Most others are unaware. The aroma of a freshly plowed field is part of the fabric that holds a farmer close to the soil. Us “old” farm kids that grew up in the days of open tractor seats and moldboard plows know that smell. As we plowed we could smell the soil. When we stopped the tractor for fuel, lunch (a snack to you youngsters), or dinner (the noon meal to you city folk) the aroma of the freshly turned soil embraced you. You would stand there, take a deep breath, and allow that aroma to settle into your lungs and senses. You felt a closeness to the soil that cannot be felt by any other sense. The aroma of soil brings a smile to your face. You get this euphoria like you get when you get a whiff of your sweetheart’s favorite perfume. That aroma and euphoria, and being enveloped by it, is all but lost with today’s tractor operators isolated in air conditioned and heated cabs listening to the satellite radio as GPS drives the tractor across the field.

Hearing was the most important sense during corn planting. Each brand of corn planter has unique sounds. For that reason alone many farmers hesitated to change brands of their corn planters. The clickity-clack of the trip wire passing through the guides; the rhythmic sounds of the gear box; the snap of the trip levers as they opened each time the kernels of corn dropped into the soil were key sounds to a successful planting season. Driving in a straight line was an obsession with my dad. Looking back to check the planter often caused a deviation from a straight line. That was an event that came with consequences. Hearing the sound of a properly operating planter as you looked straight ahead, and drove a straight line, was the most important attribute of a planter operator. Today’s planters are monitored by electronics and computers. The operator is isolated from the planters sound by the tractor’s cab. The operator is totally dependent upon the computer to determine problems and can result is excess downtime.

Picking corn was similar to planting corn. Hearing was the key sense for the operator. The first corn combine we had on the farm had a

I’m a believer in concentrating on the basics. Today, fewer people pay attention to that. Understanding the basics allows you to appreciate technology, and you always have a fall back position. During my years at John Deere a wise mentor told me, “Kid, concentrate on the basics, you’re not smart enough to make advanced mistakes.” I’ve found that to be good advice for all aspects of life and living. I am no longer involved with farm machinery, but I still have the basic knowledge of how to plant corn, harvest corn, save seeds, and plant a crop again the next year. I also know how to conduct a soil analysis without any lab equipment.

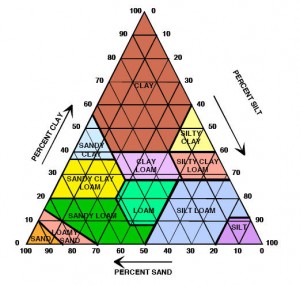

During my career, I happened into a situation where I questioned the value added by technology. I was conducting tests and needed to determine the soil type. I was familiar with the rich black soil of Iowa, and it’s unique aroma. Rich with humus, the soil had a texture and feel all its own. Soils in other states were not the same and were unfamiliar to me. The current procedure was to collect samples in quart cans, seal the cans, send them to the lab, and wait six weeks for the results of the minutest detail. Too long and too complex because I needed results today. I decided to use the old farmers approach. That approach had been completely lost on the highly educated people in charge of the lab.

In the “old days,” soil was usually typed when a farm was sold. The seller and buyer would go out to a field, dig down two to six inches, and

Haying season was also a time when the sense of smell was rewarded with the aroma of freshly cut alfalfa. This is an aroma farm kids and

One evening as I was driving home in the twilight, I went down a hill on the highway. Light ground fog was starting to accumulate in the low land at the bottom of the hill. It was a scene I had seen many times while growing up on the farm. The windows of my pickup truck were down, and the sweet aroma of freshly mowed alfalfa hit my nostrils. I looked around. Just ahead on the left side of the road was about twenty acres of freshly mowed alfalfa. I slowed down. I took deep breaths. The aroma brought back many memories of growing up on the farm. The aroma is very relaxing, and I felt mellow. For a brief time, the grief of my loss faded away.

If you want to experience the sweet aroma of freshly mowed alfalfa, drive through farm country in early June and mid-August, at least in Iowa, roll down the windows, turn off the AC, and search for a freshly mowed field. You will be rewarded with one of the sweetest aromas on earth. That aroma is just another of God’s gifts during our earthly life.