Preface

My memories of baling hay during Iowa’s hot and humid summertime of the 1950s.

Shade Tree Stories

The cool shade of a big tree brings joy to young and old. The shade was a joyous location after a humid afternoon of baling hay in the hot Iowa summertime. I hold fond memories of those days in my youth; days before responsibilities and relationships.

Working in the hot sun baling hay was just another day in the summer on an Iowa farm. Most farms had several shade trees but the most cherished were the big elm trees. Trees so big even the men couldn’t reach around them. Trees so tall they looked like giants. They were old trees, and no one seemed to know the age of the trees. Some old timers said they had been there since Moby Dick was a minnow.

For us teenagers working on the haying crew, the big elms were a place to escape the hot sun. We loved shade trees because none of the farms in our neighborhood had air conditioning. Air conditioning was a luxury. Those that had air conditioning lived in town and were considered wealthy people. Out on the farm, we slept in the damp basement on really hot nights. It was damp and clammy but at least it was cooler than the bedrooms of the house.

Baling hay was usually a four day project. When the hay was tall enough to cut, the weather forecast was checked. In those days, before satellites, weather forecasting was an art in the 1950s. Weather satellites were still science fiction, and radar was still confined to the military. The accuracy was much less than it is in 2015. In haying season, many farmers relied on the signs of nature; the signs from the clouds, the wind, the humidity, the dew, and the moon. At least one of the local farmers had an arthritic knee that was considered more reliable than the weather forecast on the radio. They were consulted often. After carefully weighing the signs of nature, consulting the neighbors, and listing to the forecast, a decision was made to cut the hay. Neighbors would also be contacted as their help and hay racks would be needed to bale and store the hay.

After cutting, the hay needed to lay on the stubble for two or three days for it to dry. The hay had to be

If the hay were allowed to dry too long, all the leaves would fall off as it was raked and baled. The greatest food value is in the leaves and would be lost if they fell off. Livestock doesn’t do well eating just stems. Determining the proper dryness for baling was an art handed down from generation to generation. The afternoon of the second day after mowing, the hay would be checked for dryness. The most common way was to grab a hand full of hay and twist the stems. The effort required to twist the hay was a key indicator of moisture content. Too much moisture required extra effort to twist. Too little moisture caused the stems to be brittle and crack. After twisting, the stems were scratched with a thumb nail and examined for moisture. The next step was to bite the stem of a stalk with your teeth to check moisture and taste. This process was repeated every half day until the moisture was judged to be correct. Moisture testing was always fun as alfalfa had a sweet taste and aroma.

My dad, Fritz, and his cousin Hans were cousins who farmed near each other. They owned the hay baler together and helped each other make hay. Together they did the moisture testing. Hans and Fritz twisted, bit, tasted, and then compared conclusions. I tagged along trying to learn the art of determining the correct moisture. The final decision went to who’s ever farm we were on.

When the dryness was determined to be correct, the order was given that tomorrow we will bale hay. This always started a frenzy of work. The hay rake and the baler were made ready. The hay racks were rounded up from neighbors. If we were baling with a wire tie baler, the leather gloves were checked for holes or tears. If we were baling with a twine tie baler, leather gloves were not required but some guys used them. The wife of the farmer doing the baling began the preparation of food for the baling crew.

The next morning, when the dew was just right, the hay was raked. Raking too early put too much moisture back into the windrow. Raking too late in the morning, with not enough dew, knocked too many leaves off the stems. The goal was to start baling just after dinner (that’s the noon meal for you city folks). Just before dinner, the hay was twisted again to check moisture and the final decision to bale was made. Dinner was eaten and off to the field we went.

There are three major jobs in baling hay, baling it in the field, hauling it to the barn, and storing it in the barn. I usually worked in the field with one other person. We took turns driving the tractor and loading the bales on the hay rack. If the hay

Photo credit: popscreen.com

Loading the sixty to eighty pound bales was hot and hard work. These were the days before sun screen and knowledge of skin cancer. We wore caps and “T” shirts. Some guys went without their shirts and their hats. Each group on the haying crew carried a water jug with them. After a couple of hours, the ice in the water jug was melted and the water was warm, but it was still wet. When we changed a full hay rack for an empty hay rack each group would pause just long enough for a drink of water. The water jug, each crew had their own, and it was passed from person to person and everybody drank out of the same spigot. Guys that chewed tobacco had to drink last then wipe off the spigot with their hand and splash a little water out of the spigot. There were no federal regulations on water jugs for haying. We all survived, never got any diseases, and turned into old codgers.

Baling hay was intense and the weather always unpredictable. The best hay was baled without being rained on after it was cut. Except for a drink of water, we didn’t take breaks. As the long hot afternoon passed we all looked toward the farmhouse and the shade tree. When the last bale was stored in the barn we would be under that shade tree. We would be in that oasis of shade cooled by a gentle breeze. The sun would still be high in the fair weather blue sky. A few white puffy clouds would gently float across the sky on a slight breeze from the south. The gentle breeze would jingle the leaves and create a pleasant relaxing sound. The sweet smell of newly baled alfalfa wafted through the farmstead on the gentle breeze. The sound of cicadas’ singing in the trees filled the air. All this we took for granted as we settled into the shade for the real treat of the day.

Lunch.

The wife had been cooking most of the day for us. She would present us with ice-cold lemonade and ice-cold sun tea. Lemonade made from real lemons and tea brewed all day in the sun. Tea bags had been placed in gallon jars of water In the early morning. They sat in the yard with the hot sun shining on them, and the tea steeped all day. As the last load of hay came to the barn, the tea was placed on ice. Sun tea is a true nectar of the gods.

After the drinks came the food; chocolate cakes and two or three kinds of fresh baked pie were set before us. Sometimes fresh cookies still warm from the oven were served. Each farm had its own specialty cake or pie that us teenage boys eagerly

The guys from the hay mow would tell about how hot it was in the mow. They would whine about the wind being from the wrong direction causing an almost breathless heat in the mow. I think some fire and brimstone Sunday sermons started out as haymow stories. They would bellyache about the bales being too loose or to tight causing them extra work. They would complain the fork operator didn’t drop the bales when commanded, causing them more unneeded work.

When the haymow crew was done, the guys from the field would start their stories. The sun was always too hot. The breeze

The person hauling the hay from the field to the barn got his turn and had stories about all the gates he had to drive through. The agony of stopping, getting off the tractor, opening the heavy gate, getting back on the tractor, driving through the gate, stopping, getting off the tractor, closing the even heavier gate, getting back on the tractor, and going to the next gate. Then, he repeated the story, with embellishments, for each gate. At least one story required details of chasing cattle or horses away so he could drive through the gate. There were also stories of all the mud holes and pot holes he had to go through and the effort it took to keep the bales from falling off the rack.

Then, it was the turn of the person who stuck the hay fork to lift the bales into the barn. His story was the bales were too

So the stories were told as we feasted upon cold drinks and luscious desserts. As teenagers, we keenly observed the art of storytelling and the skill of embellishment; a useful skill when we became young men and went on fishing and hunting trips with our friends. We all shared the joy and laughter as each story was told. Unfortunately, most of us are not nearly as good a story teller as our elders. The art of story telling has been all but lost with the advent of modern farm machinery. Today, one person does the work of many and does it inside a tractor cab with all the amenities of air conditioning, satellite radio, and comfortable seats. One big round bale holds more hay than an entire hayrack, and it was made by one person in a tractor cab. There are still stories to be told but far fewer people to listen to them because modern farm equipment allows one person to be as productive as ten people were in the 1950s. Dutch elm disease has claimed most of the big shade trees where we gathered after the last bale was in the barn.

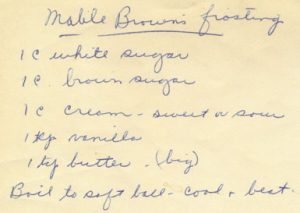

Times have changed, but we cling to the memories of hot summer days, fresh pies and cakes, the stories told under a big old shade tree, and the taste of Mable Brown’s brown sugar frosting.

IAO